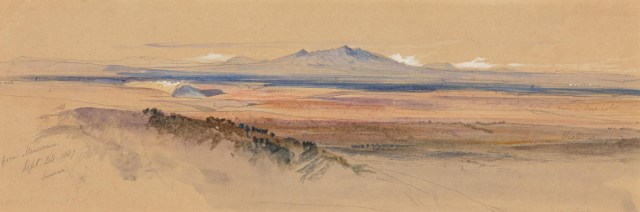

Edward Lear, Study of the Roman Campagna.

Signed ‘Edward Lear del.’ (lower left), inscribed and dated ‘Roma/1840’ (lower right)

pencil heightened with white. 41 x 27 cm (upper left corner missing), framed and glazed 63 x 45 cm.

-

Join 1,457 other subscribers

Search this site:

Edward Lear

- Biographical Essays

- Ship of Fools. All Aboard!

- Lear’s Diaries

- A Chronology of Lear’s Life

- EL. Landscape Painter and Poet

- Bibliographies and Links

- The Edward Lear 2012 Celebrations

- Letters to the Caetani Family

On Lear and Nonsense

- A Very Good Children’s Book (1865)

- Nonsense Verse, &c. (1880)

- Word-Twisting Versus Nonsense (1887)

- Concerning Nonsense (1889)

- Delightful Nonsense (1890)

- G.K. Chesterton, A Defence of Nonsense (1902)

- The Poems in Alice in Wonderland (1903)

- Limericks (1903)

- Ian Malcolm on Edward Lear (1908)

- G.K. Chesterton, Two Kinds of Paradox (1911)

- H. Jackson, Masters of Nonsense (1912)

- H. Hawthorne, Edward Lear (1916)

- G.K. Chesterton, Child Psychology and Nonsense (1921)

- How Pleasant to Know Mr Lear (1932)

- G.K. Chesterton, Both Sides of the Looking-Glass (1933)

- G.K. Chesterton, Humour (1938)

- G. Orwell, Nonsense Poetry (1945)

- George Orwell, Funny, But Not Vulgar (1945)

- Michele Sala, Lear’s Nonsense: Beyond Children’s Literature

- More Articles

Twitter Updates

Tweets by margrazCategories

- Comics (68)

- Cruikshank (4)

- Dr. Seuss (22)

- Edward Gorey (15)

- Edward Lear (1,277)

- General (139)

- Gustave Verbeek (27)

- James Thurber (3)

- Lewis Carroll (68)

- Limerick (64)

- Nonsense Lyrics (29)

- Peter Newell (87)

- Podcasts (40)

- Punch (2)

- Uncategorized (17)

- WS Gilbert (1)